By 1941 Nikuma Tanouye, his wife and their six children were well established in Torrance, California. Nikuma had learned the English language, and was a farmer working for Mr. Hiromoto also from Torrance, CA. He was also a Kendo (Japanese sword fighting) instructor. He was a member of the Shuboyo Kendo Club of Redondo Beach, CA and had been for ten years. Nikuma served as vice president. The pre-war kendo clubs were formerly branches of Dai Nippon Budoku Kai, whose headquarters were in Kyoto Japan. Dai Nippon Budoku Kai was originally designed to develop the Japanese warrior spirit in young Japanese. The literal translation would read, “The Great Japan Military Virtue Association”. Mr. Yoshinobu, on whose ranch the kendo club was housed, stated that the Shuboyo Kendo Club was not affiliated with the Dai Nippon Budoku Kai, nor any other clubs or organizations.

Nikuma’s parents were deceased and he had no living siblings in Japan. Nikuma had never made any contribution towards war relief in Japan and he had never attended any meetings welcoming Japanese Army or Naval officials. His children had never been to Japan, and he came to the United States to start a new life, and had no intention of ever going back to Japan.

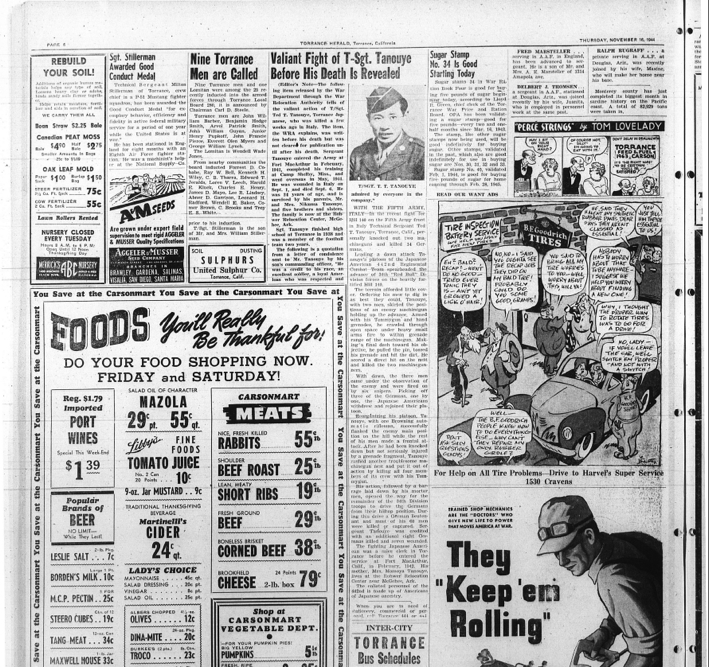

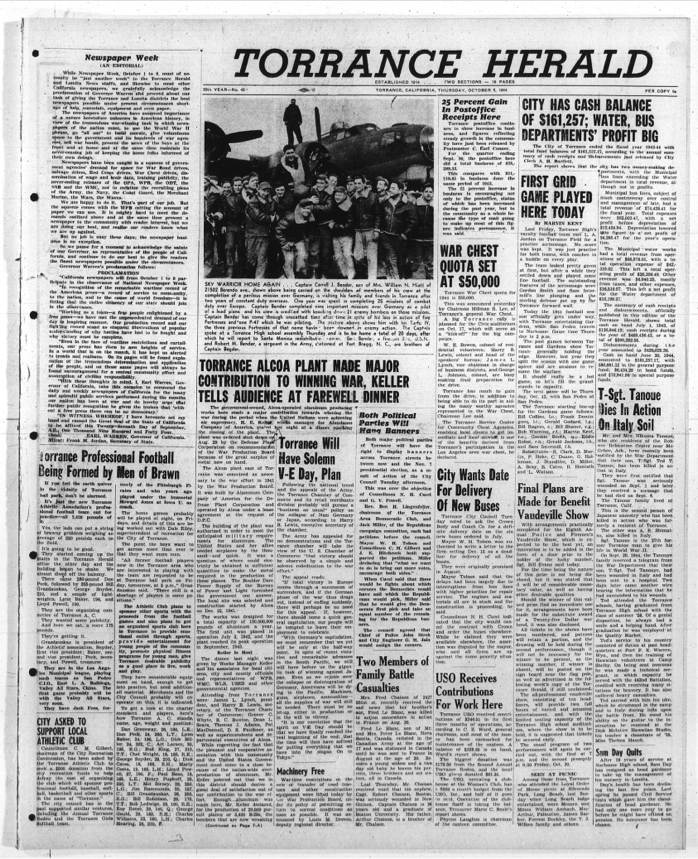

Nikuma’s eldest son, Ted Takayuki Tanouye, who to his friends was simply “Tak”, was born on November 14, 1919 in Torrance, California. His family was no doubt proud of him as he excelled in both academics and athletics, and lettered in both baseball and football each of his years in high school. Tak made Honor Roll, and was a member of the Varsity Club, Future Farmers of America, the Japanese Club and Key Club. He was also elected President of his sophomore class. An “All American” teen. Tak was also schooled in Japanese culture, learning the martial art of Kendo with his father and brother at the Shuboyo Kendo Club.

Ted Tanouye (front row, second from left)

Photo provided courtesy of the Tanouye Family

Upon graduating, Tak started working in the produce department of Ideal Ranch Market along with his friend, Ray Takayama. Ray later opened his own local store, Ray’s Friendly Market, and Tak went to work for him as head of the produce department. It was while he was at work on that morning of December 7, 1941, that he learned of the bombing of Pearl Harbor. The United States was at war, and he knew that things would never be the same. On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 which allowed the military to order more than 100,000 Japanese Americans to be forced out of their homes and relocated to remote areas of the country where they were incarcerated surrounded by barbed wire, and monitored by military guards.

Tak in front of Ideal Ranch Market

Photos provided courtesy of the Tanouye Family

December 7, 1942 changed the lives of Japanese Americans, but it was the night of February 21, 1942 that was to forever change the Tanouye family’s lives. In a midnight raid, the FBI arrested Nikuma. According to the family story that has been passed down to his granddaughter, Diane Tanouye, they did not even bother to knock. The family’s door was kicked in, and the house was raided. Her grandfather was a “proud, dignified man, a master of the martial art of kendo and the father of five sons and a daughter. The “Old World” concept of family honor was very strong in Japanese American families, and the idea that the family’s door had been kicked in during a midnight raid and that the patriarch of the family had been arrested brought great shame to the family name.” Nikuma was 56 years of age at the time of the arrest and his standing as a martial arts specialist in the art of kendo, and his standing as a respected member of the Japanese American community made him a suspect, a threat to the United States. This man who had registered for the draft during WWI was now a person of suspicious nature during WWII.

Page 1 of U. S. Department of Justice Alien Enemy Questionnaire completed by Nikuma Tanouye on February 23, 1942.

From the National Archives at College Park

Click here to read the completed document.

Gwen Granados, a federal archivist found that the first 35 Japanese nationals that were arrested after the attack on Pearl Harbor were sent to Griffith Park and placed in a makeshift jail. They were then transferred to Tuna Canyon, originally a Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camp built in the 1930s, then converted into an internment depot on December 15, 1941. While held at Tuna Canyon, which had fences topped with barbed wire, sentry boxes at each corner, and floodlights, detainees were subject to Justice Department hearings and trials.

Tuna Canyon Detention Center surrounded by barbed wire fencing, sentry boxes and flood lights.

Photo provided courtesy of the Tuna Canyon Photo Catalog

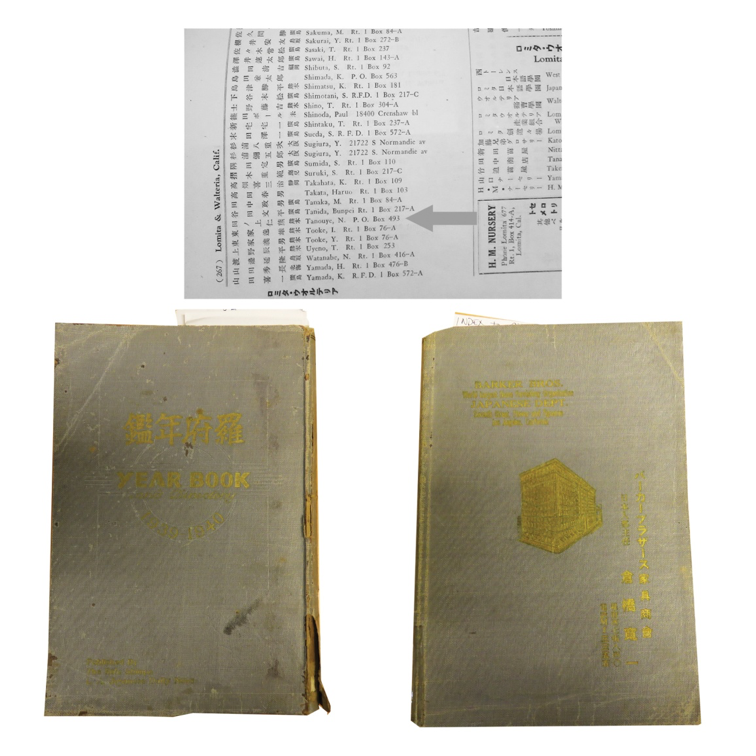

Nikuma was held at Tuna Canyon for nearly two months. During his stay he recorded names of other prisoners, and expressed his humiliation, and his distaste for the meals they were fed. He was finally paroled and transferred to join his family at the Santa Anita Racetrack, which had been converted and designated as an “Assembly Center” near Los Angeles, California. He arrived on April 13, 1942.

Enemy Alien Cards for Nikuma Tanouye

Nikuma Tanouye’s parole release document from Tuna Canyon Detention Station

From the National Archives at College Park

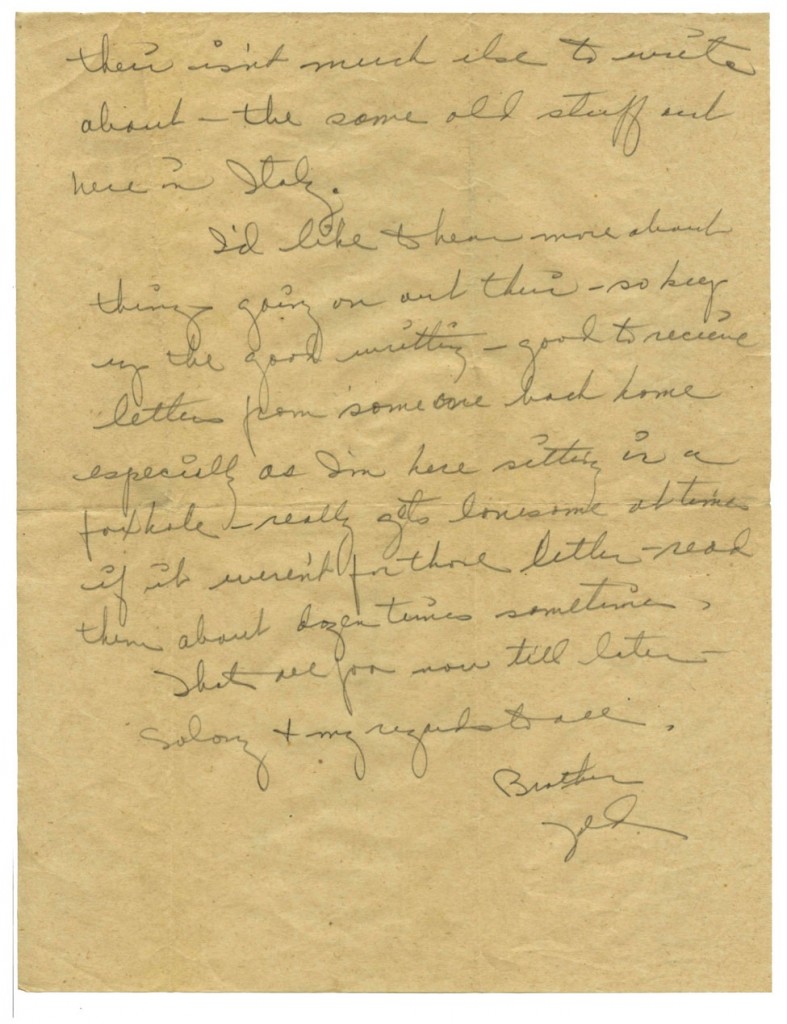

As a result of the attack on Pearl Harbor the government decided to reclassify Japanese-American men as 4C (enemy alien), exempting them from the draft Having been drafted before this policy went in to effect, Tak was inducted into the U.S. Army on February 20, 1942. The following evening of February 21st, the FBI had come to arrest his father. Some weeks later, his mother, brothers and sister were ordered to go to the Santa Anita Racetrack, now an “assembly center”. After being paroled from Tuna Canyon, Nikuma joined the family at Santa Anita where they lived for six months. On October 16, 1942, they were shipped to Camp Jerome, a “Relocation Center” in Arkansas, one of ten such camps operated by the War Relocation Authority and incarcerating an estimated 110,000 Japanese Americans. When Jerome was closed to be converted to a German POW camp, the Tanouye family was sent to Camp Rohwer, Arkansas until the end of the war.

Meanwhile Ted, who was inducted at Fort MacArthur in San Pedro, would come to be transferred to various military installations including Arkansas, Wyoming, and Mississippi. The diligence that he put into excelling in high school carried over to the military and he quickly rose in rank from Private to Technical Sergeant. He applied for officer training, but was denied, which greatly disappointed him, suspecting that his being Japanese may have been an issue. Ted’s service included duties at post headquarters at Fort F.E. Warren, Wyoming, where he trained as a cook and baker.

Collage of photographs of Private Ted Tanouye during basic training

Photo provided courtesy of the Tanouye Family

Japanese in the Hawaii Territorial Guard (HTG), which was mainly ROTC students from the University of Hawaii were dismissed. After their dismissal, the students that were with the HTG decided that they still wanted to play a role during the war and petitioned the military governor to volunteer as a labor battalion. This petition reads:

We, the undersigned, were members of the Hawaii Territorial Guard until its recent inactivation. We joined the Guard voluntarily with the hope that this was one way to serve our country in her time of need. Needless to say, we were deeply disappointed when we were told that our services in the Guard were no longer needed. Hawaii is our home; the United States, our country. We know but one loyalty and that is to the Stars and Stripes. We wish to do our part as loyal Americans in every way possible and we hereby offer ourselves for whatever service you may see fit to use us.

In February 1942, the 169 students got their wish and became a labor battalion that came to be known as the Varsity Victory Volunteers and they performed small labor jobs.

There was fear about the loyalty of Japanese-American soldiers should Japan invade Hawaii. Through the efforts of many supporters, permission was granted to form the segregated “Hawaiian Provisional Battalion”. As an active military unit they were renamed the “100th Battalion Separate” and sent to Camp McCoy, Wisconsin for training. They proclaimed the motto, “Remember Pearl Harbor”. The 100th Battalion was sent to Italy and entered battle there on September 29, 1943, near Salerno in Southern Italy. They advanced north, facing heavy enemy resistance but advanced 15 miles in 24 hours, to Benevento, an important rail intersection.

Building on the exemplary training record and success of the 100th Battalion Separate, the army decided to expand the model and formed the 442nd Regimental Combat Team which was also a segregated unit comprised mainly of Nisei soldiers. Nisei are Japanese-Americans whose parents had immigrated to the United States. Most of the officers were not of Japanese ancestry. The army first looked to the WRA camps to get recruits to fill the 442nd ranks, but they had not fully considered all of the complex factors and social pressures that might prevent these young men from volunteering from this environment of incarceration in large enough numbers to meet the needed quota. Having secured approximately 1,300 men in this initial effort on the Mainland, the army returned to Hawaii announcing the call for 1,500 men. They were overwhelmed by the response when an estimated 10,000 men came to volunteer, eager to serve their country and prove their loyalty. The 442nd chose the motto, “Go For Broke”. In Hawaiian Pidgin, this means “to wager everything”. In other words, they would risk everything and give it their all. The regiment had many soldiers whose Japanese families were stripped from their homes and most of their belongings, then put into camps, so they had this strong desire to prove their loyalty to their country, which made them more determined to conquer their fears and attain their objectives.

Tak working as a mess hall cook at Ft. Warren Wyoming in November of 1942

Photo provided courtesy of the Tanouye Family

When Ted was first transferred to Camp Shelby, he served as the Mess Sergeant for K Company. Then seeing that the position of 2nd Platoon Technical Sergeant was open, Tanouye volunteered himself, wanting to assume a more active role in the infantry. He joined the ranks of the 442nd.

The 100th Battalion was moving north in Italy. They were assigned to take the Monte Cassino Monastery. The Germans had “Clear-cut” the forest and redirected water to flood the surrounding valley, protecting the only approach to Castle Hill, the site of the castle guarding the road to the monastery. Having suffered heavy casualties after multiple assaults which stalled at walls of the castle, the High Command determined the German defenses to be too strong and ordered the bombing of the Monte Cassino Monastery. As a result the 100th Battalion was nicknamed the “Purple Heart Battalion” and held to the motto “Remember Pearl Harbor”. Soon after, the 100th began to receive its first replacements from the 442nd RTC. The 100th Battalion became the first battalion of the 442nd RTC and kept their name the “100th” in honor of their military record.

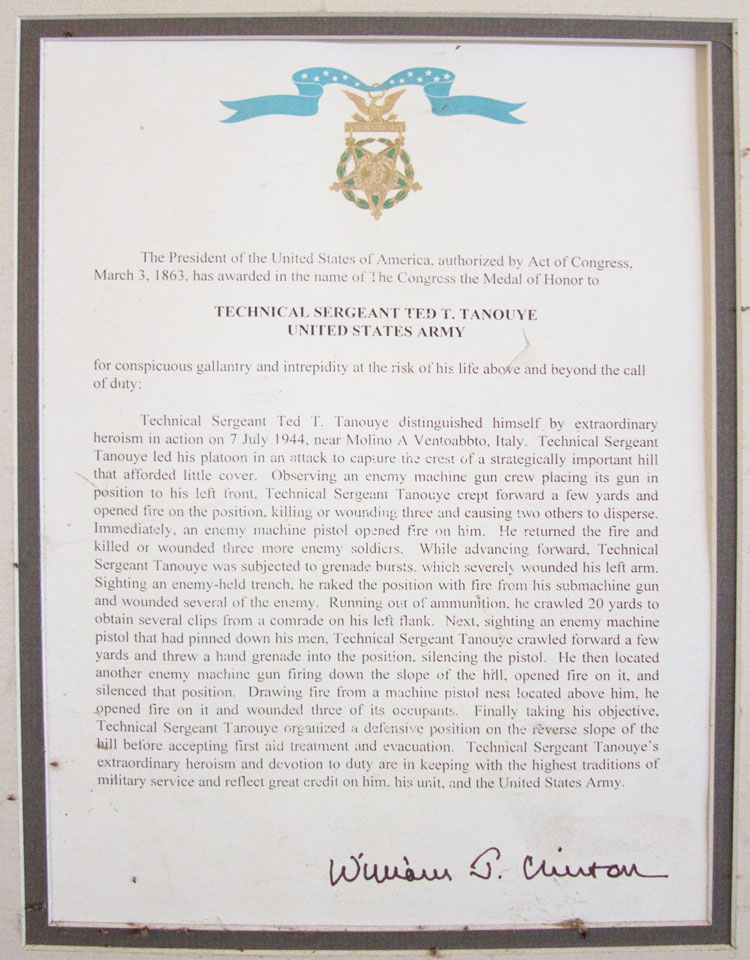

The 442nd landed at Anzio on May 28th, and joined the 100th Battalion in Civitavecchia, north of Rome on June 11, 1944. On July 7, 1944, his third day on the front line, Technical Sergeant Tanouye displayed that “Go For Broke” mentality. He led his platoon in an attack to gain control of a strategically important hill that allowed very little cover. This site was known as Hill 140, a strong line of German resistance. The enemy held the hill, and had already wiped out machine gun squads of L Company of the 3rd Battalion and G Company of the 2nd “Battalion.

Map of Italy

In a dawn attack, Technical Sergeant Tanouye, leading an advance attack on Hill 140, noticed an enemy machine gun crew to his left. The area allowed for little cover. He noticed the enemy setting up machine guns to fire on his troops. He crept forward a few yards and opened fire on them killing or wounding three men and leading two others to try to disperse. From somewhere an enemy machine gun opened fire on him. He fired back and killed or wounded three more enemy soldiers. Reorganizing his platoon, he was still intent on moving forward. He charged through heavy fire and grenade bursts, and in the process destroyed many enemy machine gunners and machine gun nests. Tanouye was wounded on his left arm but turned down medical aid. He did not give up here. Tanouye caught sight of an enemy-held trench and fired his submachine gun, wounding more enemy soldiers. Out of ammunition, he crawled 20 yards to get more clips from a fellow soldier. At that point he saw an enemy machine pistol that had pinned down some of his men, so he crawled further forward and threw a hand grenade in that direction. The enemy fire ceased. He then took note of another machine gun nest located above him, so he once again opened fire, and once again silenced the nest. Tanouye next organized a defensive position on the reverse slope of the hill. His left arm was seriously injured, but he made his mark on Hill 140. Hill 140 became known as “Little Cassino” due to the strong resistance from the Germans. By 1800 hours on this day, the Germans started their retreat.

Technical Sergeant Tanouye was sent for medical care, but would soon return to join his men as the 442nd advanced against the Germans. They faced heavy resistance as they fought on towards the Arno River.