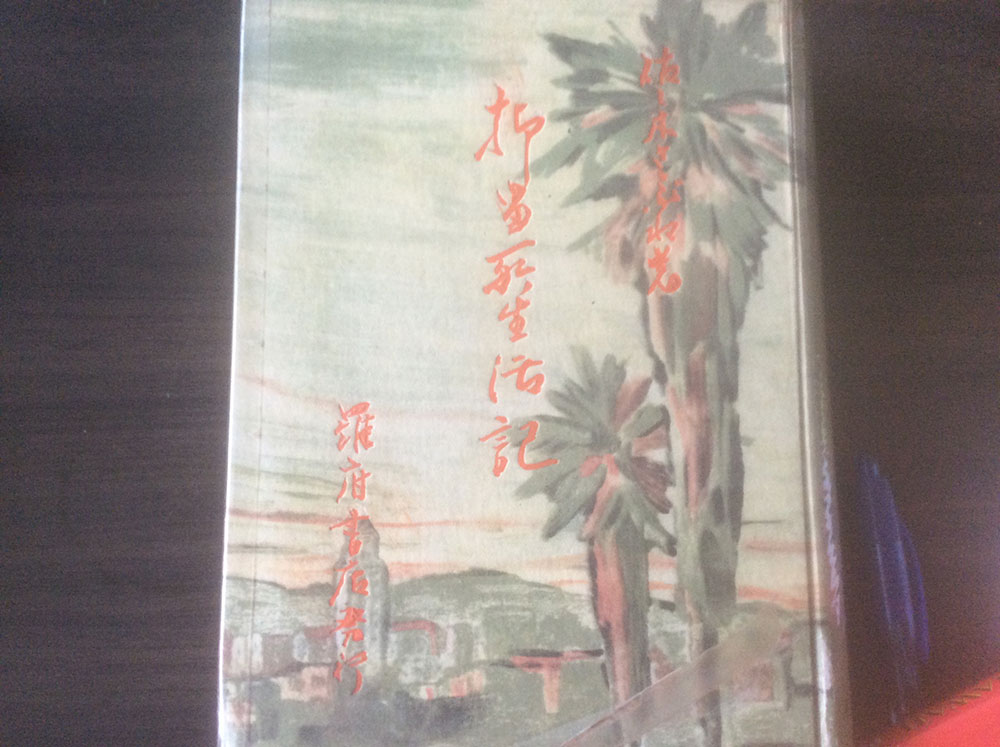

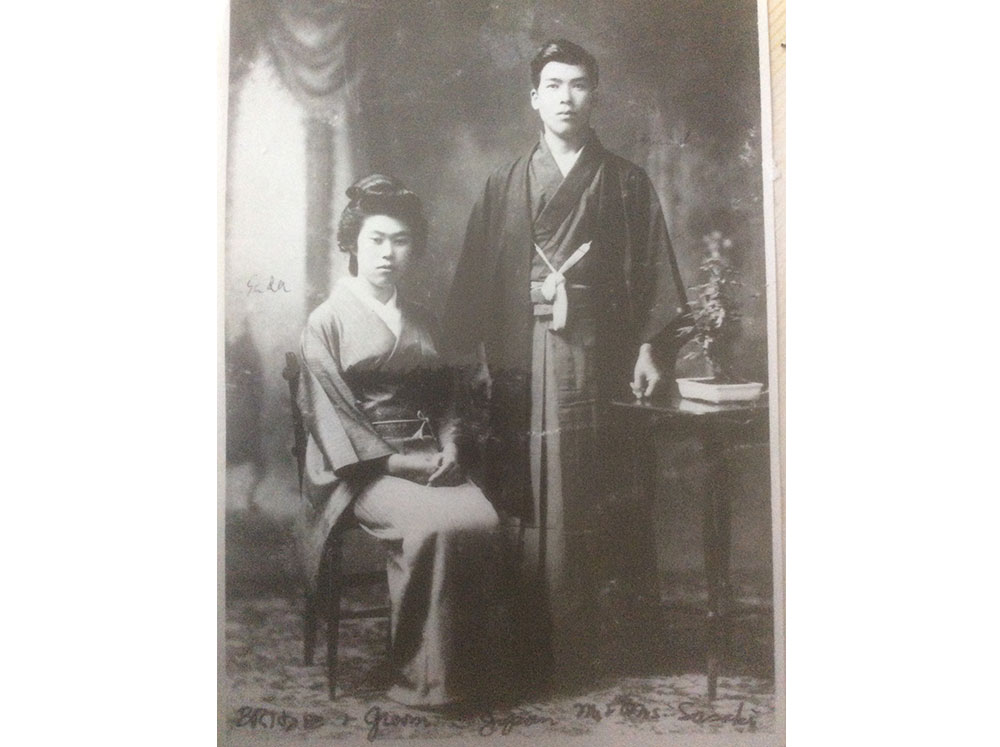

Shuichi Sasaki

(pg. 74 -)

- Then to Terminal Island

I do not know exactly when the county jail had been built, but it seemed quite new and well furnished with various facilities. The waiting room where we were herded into was very clean, sanitary, and spacious beyond compare to the police substation jail in which some of us had been put at first. It must have been used only for men: that there were eleven urinals, though without any partitioning screen, there was a drinking fountain, and a built-in bench. That was all the fixtures in this room.

There was another group of about 30 people brought into this room from the west area of Los Angeles, and some people from our group had been taken to some place else.

There was a steam heater, but the room was not very warm. Maybe because it was still early morning. All of us had been moved around throughout the night without much sleep, so many of us just lay or sat down on the concrete floor. I tried to lie down since I was exhausted from fatigue and sleepiness; however, as soon as I started to doze, a bodyache and a chill tormented me that I could not sleep nor rest my limbs.

Someone kept smoking cigarettes vacantly sitting on the narrow bench. Another paced back and forth inside this room. Some chatted in groups of three or five, but by this time we all had shared about our arrest or a war story of a thrilling air raid, that no loud or cheerful voice was heard. On the contrary, some were casting their eyes down in a manner of being sunk in thought. They might have been worrying about their family or supposing what would happen next to them.

Meanwhile the noise of the trains that went through the city started to be frequent and the window facing the courtyard grew lighter. The people who had been lying on the floor started to get up one by one, and the ones who had been sitting on the floor started to stand up or move to the bench. The atmosphere became a little more lively than before.

“It feels long when waiting.”

Someone said as if he had longed for the dawn. It was an old man I did not know.

“It will be bright soon. It doesn’t take long when the window looks like that.”

Another old man who was leaning against the wall by the door to the hallway said in a comforting manner.

“I would like something hot to drink.”

“Breakfast should be soon. Breakfast is usually early in jails and barracks.”

“That’s right. They should be feeding us soon. I don’t expect anything more than some donuts and coffee, though. See, I hear they are getting ready in the dining room downstairs.”

“Oh, I think I can smell the coffee.”

“Breakfast is nice, too, but I can’t wait until the morning comes. Then we will be settled in somewhere.”

“I agree. I can’t stand being taken around here and there, or being left alone forever like this.”

About an hour later, two police officers came in through the door on the side and said,

“All come downstairs. Follow us in a single file, O.K.?”

We followed them to the hallway, took the elevator in several groups to a few floors down, and went through another hallway to an office covered by a metal fence. There we were ordered to sign our receipt of our belongings and hand it to the officer.

“It seems we are getting our belongings back.”

“They are letting us go home then.”

“They should let us go for now, since they have examined us twice already.”

A few interpreted this in a favorable way, and many more who did not say anything seemed to put a similar interpretation on it, too. It was our hope and it felt good to think that we were being released; however, our belongings were not to be given back to us at this time. Instead, they merely handed us a new receipt with an amount of money written on it. Then the same two officers lead us further down to the ground level, and to the outside.

There were two large buses waiting for us. We got in as the officers told us to.

When the bus started to move, various theories were shared.

“We are being sent far away now.”

“I heard that there is a large prison built near Chino. I think we are going there.”

“I think we may be taken to Death Valley. They say that there is a huge detention center with a capacity of tens of thousands.”

“Since they didn’t feed us breakfast, it could be a much closer place. Maybe Terminal Island?”

“The immigration jail on Terminal Island?”

“No. There is a new one built that looks like a prison.”

While we were discussing, the bus took Alameda Street and headed south.

“That’s it. It’s Terminal Island.”

“It’ll be nice if it’s Terminal Island. It’s so close that my family will be able to visit me.”

“It must be Terminal Island that we are heading to, for sure now.”

All seemed to agree with this. Even the ones who advocated the Chino theory or the Death Valley theory took back those and said with one accord,

“It’s definitely Terminal Island.”

Terminal Island was located 25 miles south of Los Angeles, facing San Pedro and Wilmington where the pier of Nippon Yusen Company was. Actually the pier of Osaka Shosen Company was on Terminal Island.

After about 45 minutes ride, the bus drove onto Terminal Island as we expected. There were several armed guards near the iron drawbridge at the entrance.

The bus stopped near the southeast edge of the island. Far behind the ten-foot high metal fence, we saw a new concrete building. There was a sign that said, “Federal Correctional Institution.”

There was a guard with a machine gun on the watchtower watching us solemnly. Nevertheless, several seagulls were flying over and away smoothly and the harbor was calm without much waves as if it was a large lake. The scenery looked truly peaceful.

(pg. 80 – )

- A Pleasant Jail

“I’m so hungry. When are they going to feed us? Really.”

“No drinking water here, either. I was so thirsty that I asked that gardner to let me drink some of the water he had for the plants.”

“Water won’t do for me. We missed breakfast and lunch.”

“I’m out of cigarettes. If I had one, it could have been a stopgap.”

“I have my last one here. Would you like a half of it?”

“Oh, how kind of you.”

Mr. Kikuji Inoue of the Kumamoto Oversea Association’s board started to whine at last, unlike his usual cheerfulness. He received a half stick of cigarette from an old man from West Los Angeles, where he also was from. He smoked it with evident joy and said,

“What a treat. I hadn’t had one since this morning.”

Since I was also in the same predicament of being out of cigarettes, I could not help feeling special sympathy for him.

In fact, we were left alone standing outside in two rows within the metal fence of the federal prison near the side gate. No donuts or coffee were given to us and we were left standing there until late afternoon. All the smokers shared whatever was left amongst them, and every cigarette had turned into smoke by noon.

The moist wind was blowing on us relentlessly, and our hunger grew worse and worse. We had given up the hope of breakfast by noon, but we were still hopeful of lunch. Time passed one o’clock and two, and there was still no sign of food. At the end, no one was complaining of hunger or lack of cigarettes anymore.

At the entrance of the building, we were called in one by one for detailed inquiry of our name, address, occupation, and so on. Then we were admitted in; but this inquiry was not making much progress at all.

When mine was done and I was admitted in, it was almost five o’clock. We were made to take a shower first, then checked for respiratory and sexually transmitted diseases, and our weight and height were recorded while we were still naked. Then we were clothed in a prison uniform without buttons that was faded from washing. After our fingerprints and picture with a number were taken, we were led through many rooms and hallways to the east end of the building facing San Pedro Harbor. It was a large room, or rather a hall, that was 100 feet long, and 40 feet wide. There were more than 100 beds arranged in four rows, and the left two rows were bunk beds. There were four windows each on the east side which was facing the harbor, and the west side which was facing the courtyard. Both sides were wrapped by the passageway of the guards, but it was not so unpleasant since there were no iron bars to interrupt our views, as in the city and the county jails. Everything looked new and the room was bright. There was a new style of fan heater, the restrooms were on the right side at the end of the room, the shower room was on the left, and there was another good-sized room connected to this room to be used for meetings and smoking. Overall, it was a well made and convenient facility.

Our guard was a short and mean looking man with hard eyes. He gathered everyone and said,

“Whoever comes here must obey the rules of this place. Blankets, towels and pillows are going to be issued right now, so go to the next door in an orderly manner. Then everyone makes his own bed in the exact same way. The crease of the sheets has to line up from here to the other end of the room. Understood? And we don’t call your name, but your number, so memorize your number. When called, respond ‘Yes, sir.’ clearly. Understood? Now, come follow me to the next door in a single file.”

We, a group of about 70 by this time, obediently followed him and received the supplies: mattress, sheets, two blankets, comforter, pillow, pillowcase, towels and so on. Everything was brand new and the blankets were marked with “U.S.” as the emblem of the federal government. We made our beds as instructed.

In this way, our family names that we had been freely and proudly using since our childhood, and the names that had been given by our parents, were taken away. Instead, we were given numbers like criminals, and we were to respond with the respectful address for the guard who would call us by those numbers. I was given a number of 6071. Mr. Sakakura’s was 6070, so he took the upper bunk and I took the one right under him. My right side neighbor was Mr. Bunshichi Okuno of Mikawaya Confectionery and my left side neighbor was Mr. Mikitaro Sato whom I mentioned before.

After the bed-making, we were led in two files through the courtyard diagonally to the dining room on the other side, and finally given a supper after 24 hours. The food was not as bad as expected. The coffee did not have much flavor at all, but to our surprise, it was sweetened with a small amount of sugar.

We were made to form a line at the entrance to the dining room, moved slowly in an orderly manner, took a plate — 1.5 feet long, a foot wide, alloy made plate, with six hollows — were served several things on it, sat at a table orderly and ate quietly under the watch of 7 to 8 guards surrounding us. This made us feel the sorrow of prisoner’s life. However, we were in high spirits despite the hardship of this whole day. Because we knew that this was not a result of our action that would haunt our conscience, but merely a part of the injury caused by the war.

(pg. 88 – )

- The First Night

The regulations of this prison were: rising at 6:00 a.m., retiring at 9:30 p.m., breakfast at 7:00, lunch at 12:00, supper at 5:00, roll calls at 6:30 a.m., 11:30 a.m., 4:30 p.m., and 9:00 p.m. Another patrol was to be made around midnight. We were allowed to smoke only in the smoking room, two or more people were not to sit on a bed, no metal object was allowed on us at any time, and so on.

On that day, toward evening, some heavy bombers and fighters of the Navy and the Army flew over us one by one. Some made a formation of three and flew above us in a large half circle and away to the direction of Palos Verdes Mountains. The sight suddenly made us feel overwrought. The same roaring kept audible right above us without ceasing until the night fell. Moreover, our lights were not turned on and the darkness made it even more gruesome.

At 9 p.m., the alarm went off in darkness and we all stood straight by the bed as we had been ordered for the first roll call. About 20 minutes later, we all slipped into the assigned bed. Some kept talking even after that.

“The bed is not bad. I think I’m going to sleep well tonight.”

“I’m exhausted.”

“This place shouldn’t be too bad if it’s not for too long.”

“I agree. It’s merry that there are so many of us here together.”

“I wonder how the war situation is?”

“I suppose the reports on Japanese news about Hawaii were correct.”

“Sure they were. What a tremendous thing they have done.”

While we were still talking, the guard’s flashlight approached the room, and a group of Japanese people followed him. The guard was making them choose their bed in darkness by groping. Some familiar voices were recognized.

“That’s Mr. ****, isn’t it?”

“Yes, it is. He’s arrived late.”

“There are some twenty or thirty people.”

“I wonder who they are?”

“We’ll see tomorrow morning.”

We kept talking in a low voice with the people in neighboring beds so the guard would not hear us.

The following morning, we found out that the new arrivals were mostly from Los Angeles and I knew most of them well. Thirty two or three new arrivals and us, who had arrived earlier made a group of one hundred and seven. I am not able to list all the names here, but these are some of the names, other than those ten people I already mentioned, whom I had spent time with in the city jail:

Kengoro Nakamura (president of Central Japanese Association); Kichitaro Muto (vice president of the above); Jiro Fujioka (accountant of the above); Gentaro Bessho (same as above); Shiro Fujioka (former chief secretary of the above); Shungo Abe (former president of Los Angeles Japanese Association); Kurakichi Kaneko (vice president of the above); Kohei Shimano (same as above); Kinichi Tada (accountant of the above); Tomomi Yamashita (same as above); Katsuya Kawano (former vice president of the above); Susumu Hasuike (president of Southern California Fruit Union); Mitsuhiko Shimizu (former president of Los Angeles Japanese Association); Jutaro Narumi (owner of Asia Trading); Isamu Rikimaru and Mataji Rikimaru (Rikimaru Brothers Agricultural Trading); Taiji Kita (co-owner of Star Agricultural Trading); Motoo Noritake (president of Sunrise Soda Manufacture); Choichiro Shirakawa (hotel owner and union counselor); Katsuji Uemura (owner of Fukushimaya Hotel); Yoshitaro Sasahara (former president of Hiroshima People’s Association); Isamu Sekiyama (doctor); Uich Iwata (owner of Kogetsu); Sojin Suzuki (chief editor of Rafu Shimpo); Sueji Nishimura (president of Pasadena Japanese Association); Tomoki Iwanaga (Salvation Army Lieutenant); Ryuji Tatsuno (Southern California Rank Holders Association board); Eizo Maruyama (Central Japanese Association executive); Masamichi Yamamoto (president of Southern California Wakayama People’s Association); Kuichiro Nishi (Gardner’s Union executive); Meitaro Yoshii (entrepreneur); Jihei Kuga (hotel owner); Masakatsu Fujita (assistant treasurer of Los Angeles Japanese Association); Michio Ito (dance master). There were also elderly men like Futaro Hiraiwa of Pasadena (82), Gisuke Sakamoto, an elder statesman of West Los Angeles (73), and Chozaburo Okumura of Los Angeles (72).

Most of these people had lived in the United States for many years, having been well known for their unselfish contribution to public works and American society in many ways. They were prominent and indispensable figures especially for the Japanese society in the United States.

Nevertheless, when the morning came, all these people were wrapped in prison uniforms which were without buttons. Some tied the waist of the pants with a string, some rolled up the hems of large baggy pants, and some uniforms had already been torn five to six inches. All uniforms were faded from washing and these men looked truly shabby in them.

President Komai, wearing the same prison uniform as others, was remarkably cheerful from the very early morning and volunteered to be an organizer for the housekeeping chores. The people who received assignments started to work handling a broom, a mop, or a bucket.

Others gathered in the smoking room, which had been cleaned, and chatted.

“The roaring of the airplanes above us kept me awake all night. It was hard because I was so tired and wanted to rest.”

“I fell asleep all right and did not know, but why were those airplanes flying around here?”

“For defending the coast or night time drills, maybe.”

“I don’t think so. I think they left to reinforce the Hawaiian air force in a large formation.”

“That makes sense. I heard that the damage is severe over there.”

“That may be it, then.”

“That is it, I’m sure. By the way, don’t they turn on the light at all here during the night? I had to choose a bed in darkness, and I got one without sheets or a pillow.”

“I got it worse. After I chose a bed, I went to the bathroom, and I could not find it again when I returned.”

“Oh, so that was you who was moving around me with stealthy steps. I thought it might be a burglar. I was thinking that I must be careful since this place is a nest of specialists, you know.”

“Don’t be silly. All our belongings were taken away and we don’t have anything that we need to be careful for.”

“I do.”

“How come? Have you smuggled in some cash?”

“It’s not cash. It’s my dentures. I put my dentures under my pillow when I sleep.”

“Ha, ha. Dentures. I didn’t think of that. But it is inconvenient if we have to spend every night in darkness.”

“It’s not every night. Last night was the first time. It was the blackout order.”

Said the person whose name was Ohashi. He had been in this place for smuggling industrial use diamonds.

“So, that was the blackout order. Come to think of it, the guard did look a little nervous.”

“The guard doesn’t say anything about it, but other prisoners are spreading rumors that Japanese fighters may fly over here to attack anytime. I think that could be true.”

“Aren’t the prisoners frightened?”

“No, they’re not. They are shrewd rascals.”

“Some may be thinking that an airstrike would be their chance to escape.”

“Probably. There are some Italian prisoners of war, too.”

“Where were they arrested?”

“They sabotaged the ship. They blew it up.”

“Oh, I read about it in the paper.”

“That’s them.”

Meanwhile, the cleaning was completed and some went back to the bedroom. Small groups of three or five were formed here and there, and they chatted.

The majority stayed in the smoking room. Some talked brave war stories, and some discussed the general situation of the world. It was quite lively there.

However, as for cigarettes, none had any. It was a pitiful sight when there was not even a wisp of smoke amongst so many of us gathered.

(pg. 95- )

Please contact remembertunacanyon@gmail.com to make a request for the rest of the translated diary.

About the Contributor

Yoko was born in Kumamoto, Japan and moved to the United States to further her education. While she was a student at Cal State Northridge studying anthropology, she worked for the San Fernando Valley Japanese Language Institute. She lives with her husband in Santa Paula, CA., and enjoys serving as a volunteer, teaching ESL to adults in her community, and engages in continued education opportunities to further her knowledge and skill as a teacher.